Global stages like the Super Bowl halftime show or the Olympic opening ceremony are often framed as spectacle—entertainment stripped of context. Yet when culture is deployed deliberately, these platforms become sites of power: places where history, labor, and identity are asserted rather than diluted. Two recent examples illustrate this clearly—Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl LX halftime show and Stella Jean’s designs for Haiti’s Olympic uniforms. In both cases, clothing and symbolism functioned not as ornament, but as narrative strategy.

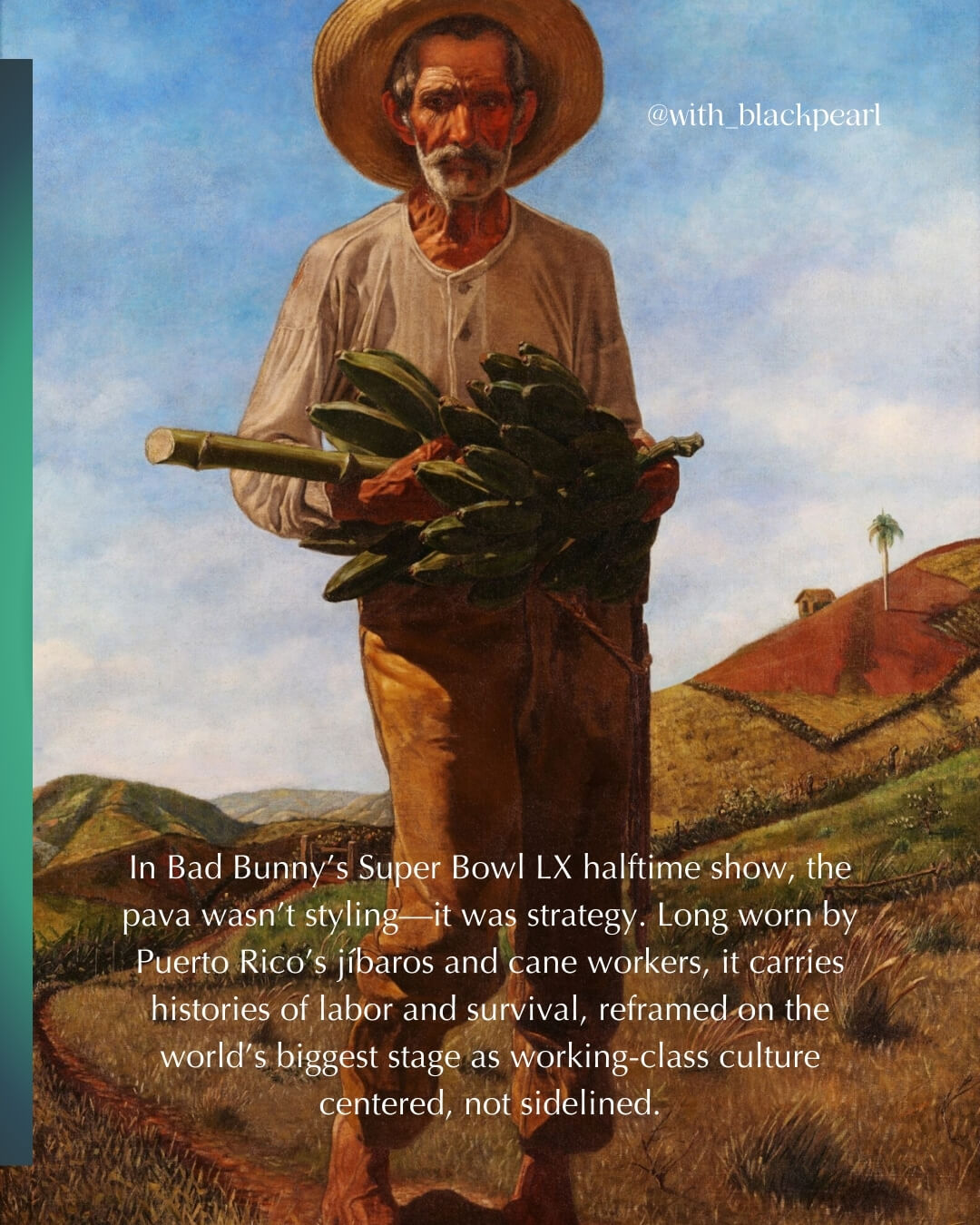

At the Super Bowl, watched by more than 100 million viewers globally, Bad Bunny centered the pava, a palm-woven straw hat historically worn by Puerto Rico’s jíbaros—rural farmers and sugarcane workers. The pava is inseparable from agricultural labor, survival, and working-class life. Outside Puerto Rico, it is often romanticized or reduced to folklore. On the world’s most visible entertainment stage, Bad Bunny reframed it as contemporary cultural language. The message was direct: working-class culture is not peripheral—it belongs at the center of global visibility.

The pava also shaped the musical logic of the performance. Its presence framed the roots of bomba and plena, genres formed within Afro-Taíno and working-class communities. Afro-Taíno refers to the intertwined African and Indigenous Taíno heritage that defines much of Puerto Rico’s cultural fabric—particularly its rhythms, communal traditions, and relationship to land. The visual of dancers wearing pavas widened this frame, linking agricultural labor to the music that emerged from it. Land, labor, and rhythm were presented as a single lineage rather than separate aesthetics.

This intervention carried a material dimension as well. Traditionally hand-woven from renewable palm leaves, the pava foregrounds sustainable, place-based craft. In an era dominated by synthetic fashion and fast-production cycles, its visibility quietly challenged prevailing fashion norms. It demonstrated that biodegradable materials and human labor can carry as much cultural force as luxury branding or technological spectacle—especially when rooted in living tradition.

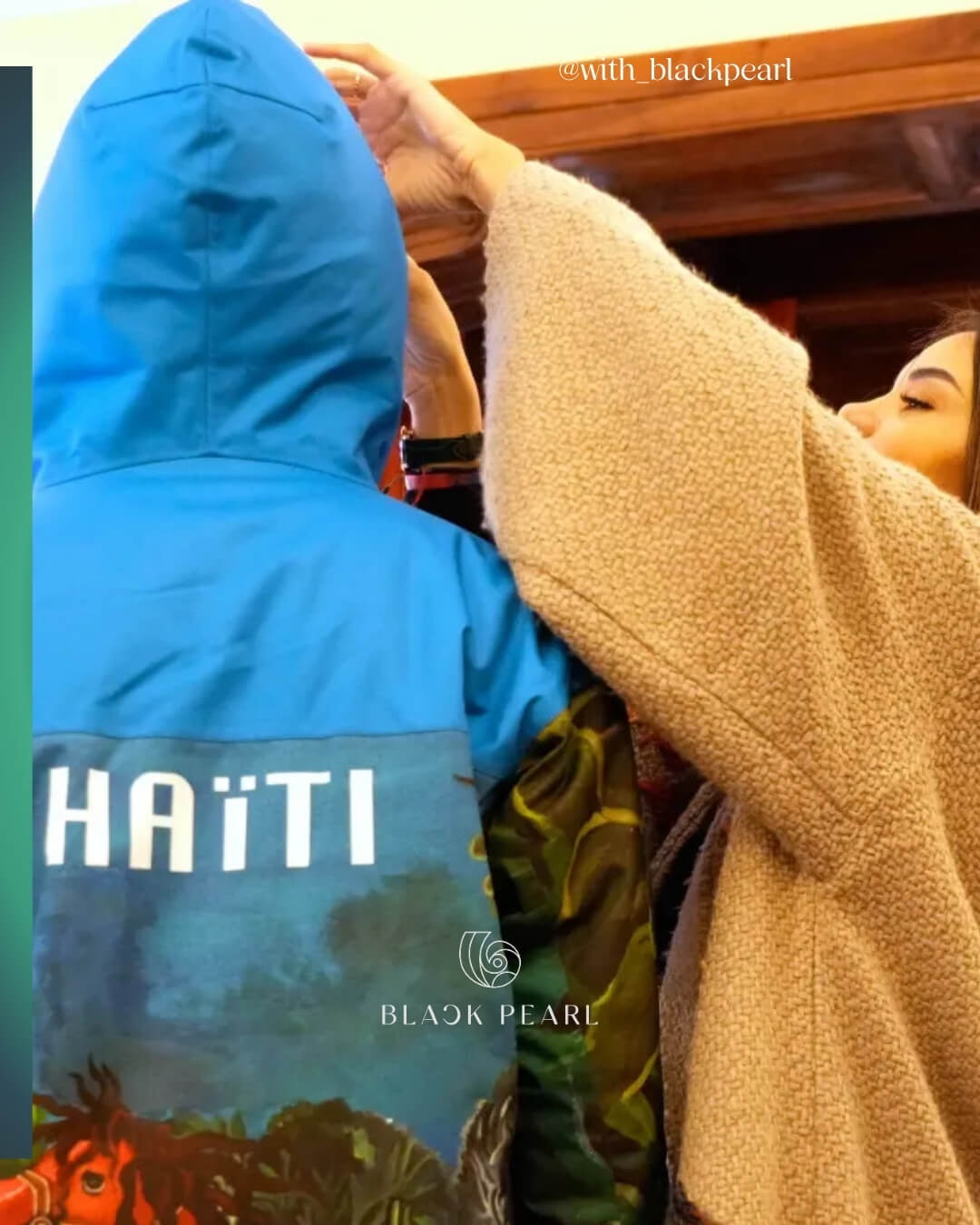

A similar strategy shaped Haiti’s Olympic uniforms. Haiti’s participation in the Winter Olympics alone disrupts assumptions about geography and belonging in winter sports. Jean treated that presence as intentional visibility rather than novelty. She has described the uniform as “a few meters of cloth” tasked with carrying Haiti’s entire history—revolution, diaspora, and resilience—through symbolic design.

The original uniform design featured Toussaint Louverture, leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first Black head of state in the modern world. Shortly before the ceremony, the International Olympic Committee ruled the image a violation of Olympic rules prohibiting political symbolism. With limited time and no additional budget, Jean was forced to redesign the uniforms days before their debut.

Rather than erase meaning, she adapted. Louverture’s figure was removed, but the red horse—drawn from Edouard

Rather than erase meaning, Jean adapted the design. Louverture’s figure was removed, but the red horse—drawn from Edouard Duval-Carrié’s artwork—remained, carrying the idea of revolutionary motion and endurance and reinforcing Jean’s belief that history continues even when figures are censored.

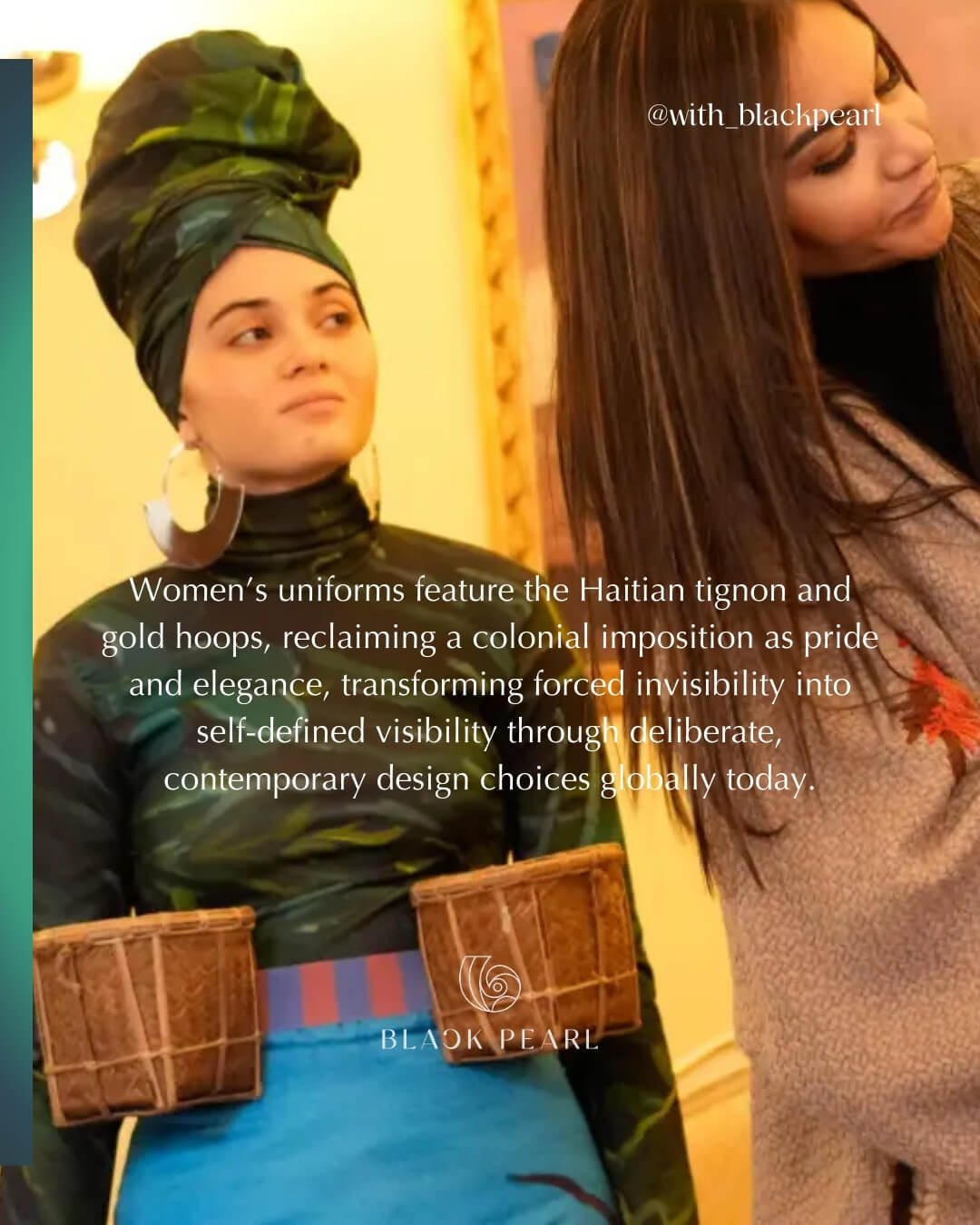

The women’s uniforms followed the same logic through the reclamation of the Haitian tignon. Once imposed under colonial rule to enforce control and invisibility, it was reintroduced with gold hoop earrings as pride and elegance, transforming restriction into self-definition and continuity.

These uniforms were never about medals. Amid political instability, migration, and humanitarian crisis, they operated as cultural soft power, projecting dignity and historical agency rather than collapse. Rather than centering narratives of collapse or deficit, the uniforms projected dignity, historical agency, and continuity. They offered an alternative global image—one grounded in revolution, craft, and self-representation.

What connects these two moments is restraint as much as boldness. Neither relied on slogans or overt messaging. Instead, they trusted audiences to read symbols embedded in material culture—hats, headwraps, silhouettes, color. This is how storytelling survives regulation and spectacle: through compression, adaptation, and intent.

On the world’s most mediated stages, identity is often simplified for consumption. These interventions resisted that flattening by keeping labor, land, and lineage visible, proving that culture moves forward even when its figures are constrained. They were not just moments of fashion or performance, but demonstrations of culture as power at scale—showing how storytelling endures when identity is treated as authorship, not aesthetic.